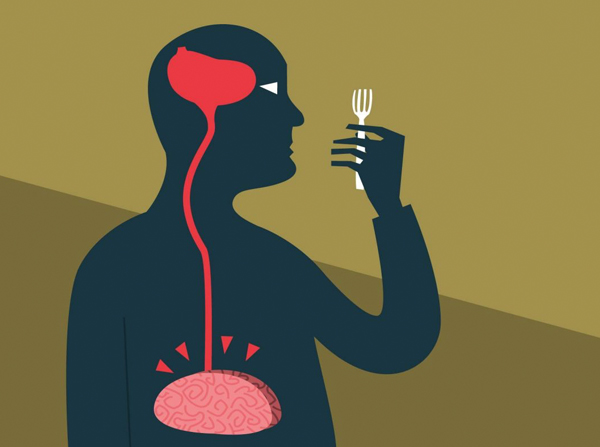

Scientists have figured out how your brain tells you that you are hungry. They found that a neuropeptide associated with appetite is sent into the cerebrospinal fluid to connect with neurons responsible for alerting hunger. (Illustration/iStock)

A USC study shows the brain’s plumbing system serves double duty, flushing waste and channeling a hunger molecule that tells you when you should eat.

“People usually think of brain cells as communicating signals through the synapses between them,” said Emily Noble, a postdoctoral biological sciences researcher at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. “We are showing that the brain has another complementary way to communicate by sending these signals into the cerebrospinal fluid.”

In cell-to-cell communication, the neurons are discretely passing notes to individual neurons or other cells. However, cerebrospinal fluid distributes a newsletter with many subscribers.

Scientists have long known that signals are sent from cell to cell or through release into blood vessels. The study, published today in the journal Cell Metabolism, shows that the brain regulates some processes by releasing and dispersing molecules, and in this case, a neuropeptide, through cerebrospinal fluid.

Hunger hormone: one fluid, many purposes

Cerebrospinal fluid has three chief assignments. First, its grueling eternal task is buoyancy, like the Greek Titan Atlas supporting the brain. Second, it acts as a cushion after a blow to the head. Third, it is the brain’s sewer system, clearing away metabolic waste.

As neuroscience technologies have advanced, scientists have seen indications that what is sometimes dismissed as sewage actually has a role in the brain’s regulation of behaviors such as stress, energy balance and reproduction.

“The cerebrospinal fluid had been historically thought more of as a metabolic wasteland,” said Scott Kanoski, the study’s corresponding author and a USC Dornsife assistant professor of biological sciences. “But what we are showing is that the fluid is an active mechanism for communication in the brain.”

Hunger peptides

For their study, the researchers focused on the molecule melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH). This neuropeptide is generated by neurons in the brain’s hunger center, the lateral hypothalamus, at the base of the brain just above the pituitary gland. MCH stimulates appetite. It also can reduce energy burn.

Through a series of experiments with rats, the researchers stimulated release of the hunger peptide and then tracked it in the cerebrospinal fluid.

“When we released MCH into the cerebrospinal fluid, the animals would start eating,” Kanoski said. “When we reduced the levels of the molecule, then we saw the opposite effect and the animals would eat less.”

Based on their findings, the researchers determined the peptide’s release is likely influenced by a circadian clock and a daily mealtime routine.

Drug developers are interested in creating pharmaceuticals that would target the MCH system to control appetite, and thereby address obesity and other weight-related health problems.

The researchers have some lingering questions about the hunger molecule that they hope will be answered with further investigation: Is MCH released from the brain in some special form that protects it from damage or other degradation? How exactly does it travel into the cerebrospinal fluid and where does it go from there?

Kanoski added that they wonder what other behaviors, besides feeding, the cerebrospinal fluid helps to regulate.