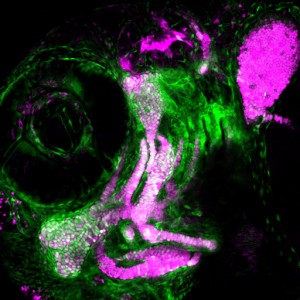

A three-day-old zebrafish head skeleton with newly differentiated cartilage cells (magenta) emerging from a pool of skeletal progenitor cells (green) (Image by Lindsey Barske)

Timing is everything when it comes to the development of the vertebrate face. In a new study published in PLoS Genetics, USC Stem Cell researcher Lindsey Barske from the laboratory of Gage Crump and her colleagues identify the roles of key molecular signals that control this critical timing.

Previous work from the Crump and other labs demonstrated that two types of molecular signals, called Jagged-Notch and Endothelin1 (Edn1), are critical for shaping the face. Loss of these signals results in facial deformities in both zebrafish and humans, revealing these as essential for patterning the faces of all vertebrates.

Using sophisticated genetic, genomic and imaging tools to study zebrafish, the researchers discovered that Jagged-Notch and Edn1 work in tandem to control where and when stem cells turn into facial cartilage. In the lower face, Edn1 signals accelerate cartilage formation early in development. In the upper face, Jagged-Notch signals prevent stem cells from making cartilage until later in development. The authors found that these differences in the timing of stem cells turning into cartilage play a major role in making the upper and lower regions of the face distinct from one another.

“We’ve shown that the earliest blueprint of the facial skeleton is set up by spatially intersecting signals that control when stem cells turn into cartilage or bone. Logically, therefore, small shifts in the levels of these signals throughout evolution could account for much of the diversity of shapes we see within the skulls of different animals, as well as the wonderful array of facial shapes seen in humans,” said Barske, lead author and A.P. Giannini postdoctoral research fellow.

Additional co-authors include: Amjad Askary, Elizabeth Zuniga, Bartosz Balczerski and Paul Bump from USC; and James T. Nichols from the University of Oregon.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE018405 and K99/R00 DE024190), the March of Dimes, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (5T32DC009975) and the A.P. Giannini Foundation. The USC Office of Research and the Norris Medical Library funded the bioinformatics software and computing resources used in the analysis.

By Cristy Lytal