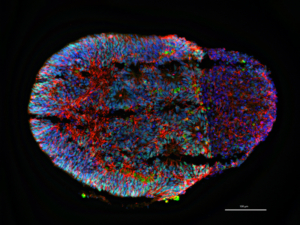

Twenty-day-old cortical organoid (Image by Tuan Nguyen/Quadrato Lab)

Maybe a child misses a developmental milestone, such as rolling over, or saying that first word. Perhaps the child also falls down due to seizures, or develops symptoms of an autism spectrum disorder. Eventually, a doctor pinpoints the cause: a rare and spontaneous variant in a gene called SYNGAP1, which leads to a variety of debilitating conditions that might include intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorders. As of now, there is no cure.

To help children with this rare syndrome, Ashley Evans and Mike Graglia founded the SynGAP Research Fund (SRF), which recently donated $46,250 to USC Stem Cell researchers Marcelo Pablo Coba and Giorgia Quadrato. Coba’s lab is at the Zilka Neurogenetic Institute, and Quadrato’s lab is at the Eli and Edythe Broad CIRM Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

“I’m thrilled that SRF is supporting their work,” said Graglia, whose son has a SYNGAP1 variant, and who serves as the managing director of SRF. “Dr. Coba has spent hours letting us pick his brain and ask questions about his papers related to SYNGAP1. He also told us about his exciting new collaboration with Dr. Quadrato, who uses stem cells from patients with the SYNGAP1 variant to grow 3D networks of human nerve cells, called brain organoids.”

The scientists will study these patient-specific brain organoids, mapping the electrophysiological and genetic activities of different types of nerve cells. They will then explore several interventions, such as drug-like molecules, gene editing, and cell transplants, to see if they can modify these activities.

Coba first connected to SRF thanks to the organization’s Science & Medicine Lead, Hans P. Schlecht, MD. As a physician, Schlecht responded to his son’s diagnosis of Syngap Encephalopathy by learning as much as possible about the variant. In 2017, he was browsing through SYNGAP1 related projects in the NIH RePORTER, an online database that provides details about medical research supported by federal tax dollars. Schlecht found Coba’s name and reached out by phone. Not long after this first conversation, Coba offered to meet in person and share even more about his research.

“A doctor is assessed on the three As: affable, available, and able,” said Schlecht. “Coba is all of these. He is easy to talk to, he replies to calls and emails, and he’s a capable scientist.”

In 2018, Quadrato joined USC as an assistant professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. She brought with her an expertise for growing brain organoids over a period of nine months in the laboratory—allowing the nerve cells to mature and diversify in ways that recapitulate some limited aspects of the extraordinary brain development that takes place during a fetus’ nine months in utero.

In 2019, she was awarded $100,000 by the Donald E. and Delia B. Baxter Foundation to use patient-derived organoids to investigate the role of SYNGAP1 in human brain development.

To further tap into the potential of organoids to enhance our understanding of SYNGAP1 variants, Quadrato began collaborating with Coba, who is an associate professor of psychiatry and the behavioral sciences at the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School.

“Thanks to this support from SRF and the Keck School, we have the means to purchase an incredible new piece of equipment called the MEA Willow System, which allows us to visualize how patient-specific brain organoids function, as well as how they react to potential treatments,” said Quadrato. “It is a truly groundbreaking technology created by a collaboration between Leaflabs and the Synthetic Neurobiology Group at MIT.”

Coba added: “We’re grateful for this generous funding that allows us to use the latest technology to advance our research collaboration. I’m also personally thankful that I’ve had the privilege to connect with SRF parents and patient advocates throughout the years. Their dedication and passion reaffirms the critical importance of the work that we do every day in the lab with the goal of finding better treatments for these patients.”