As a husband and father, an emergency medicine physician and volunteer medic with the San Luis Obispo Sheriff ’s Office Special Enforcement Detail, Kristopher Lyon, MD, had an increasingly busy life. And a noisy one.

Then one day he couldn’t hear his wife, Rachel May, speaking as they drove in the car, and he got worried. The diagnosis deepened his concerns: otosclerosis.

Derived from the Greek words for ear(“oto”) and hard (“scler-o”), otosclerosis is an abnormal bone growth that fuses the bones of the inner ear together in an immovable mass, preventing the transmission of sound. The progressive hearing loss typically begins in the early 20s, but many people don’t become aware until their 40s or 50s. Lyon was only 35.

Lyon, who has no known family history of otosclerosis, was determined to identify “the best doctor for the job,” he said. He found John S. Oghalai, MD, an internationally recognized otolaryngologist with expertise in ear and skull base surgery and now chair of the USC Tina and Rick Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery.

At the time, four years ago, Oghalai was on staff at Stanford University. Lyon, who lives in San Luis Obispo and works in Bakersfield as an ER doctor and head of Kern County’s Emergency Medical Services, went to see him.

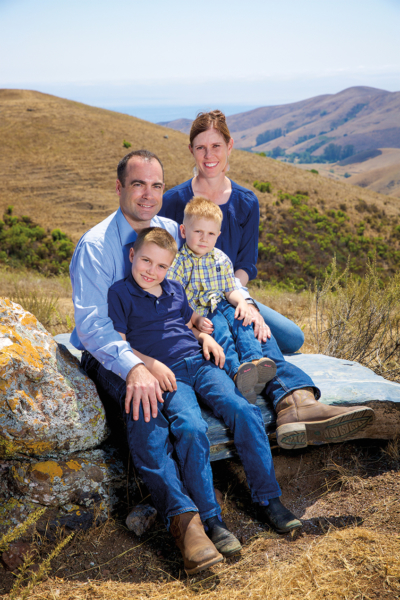

Kristopher Lyon first noticed he had hearing loss when he could not hear his wife talking. (Photo/Phil Channing)

The good news was that Lyon had the form of otosclerosis in which the bone overgrowth immobilizes the stapes bone in the middle ear, causing conductive hearing loss. In a second, more difficult-to-treat form, the ossified bone affects the entire bone around the cochlea, requiring a cochlear implant. “That diagnosis meant we could treat him with hearing aids or surgery,” Oghalai said, “both of which help bypass the fixation spot and restore hearing.”

Lyon first tried a hearing aid in his right ear, unsure how it would affect his work and family life. He soon discovered “there’s no good method of using a stethoscope with one bad ear and one good ear,” he said. And if he took his hearing aid out at night when he slept, he couldn’t hear his son, Owen.

So Lyon opted for a stapedectomy, an intricate outpatient procedure done under local or general anesthesia. “It’s one of the most delicate surgeries that ENT (ear, nose and throat) physicians do,” Oghalai said.

In fact, most ENT physicians prefer to refer their patients to expert surgeons like Oghalai. Working with a high-powered operating microscope, he removed the arch of the stapes bone in Lyon’s right ear. He then used a laser to make a tiny (.7 mm) hole and secure a lightweight titanium prosthesis .6 mm in diameter.

Lyon could hear out of his right ear again, but his left ear was already showing signs of trouble. He hoped he could beat the odds. Yet within several months, the precipitous hearing loss was too severe to ignore.

By then, both men’s lives had changed. Lyon and May had a second son, Noah. Oghalai had joined the team at the USC Caruso Department of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, drawn, he said, by “the most enthusiastic and committed group of faculty, staff and trainees I have ever seen.”

That was all Lyon needed to know. His confidence in USC had another, family origin: His parents met at and graduated from the university. His father, the late attorney and conservationist Roger Lyon, was an All-American swimmer for USC, while his mother, Susan Briles Lyon, majored in art history.

Once again, Lyon opted first for a hearing aid in his left ear, waiting until his sons got a bit older. This past May, Lyon, now 39, had his second stapedectomy, this time at Keck Hospital of USC.

Following the hour-long procedure, Oghalai packed Lyon’s ear to protect the ear drum during recovery. When Lyon returned to USC a week later, Oghalai removed the packing. The sound, says Lyon, was “quite loud.”

For Oghalai, the procedure also is a source of satisfaction. This form of hearing loss can actually be fixed. “You can completely restore a sense that was lost,” he said, “and for most patients, their hearing is like it was when they were kids.”

Because otosclerosis symptoms can be confused with age-related hearing loss, Oghalai suggests getting a hearing test for a proper diagnosis.

With his hearing fully restored, Lyon is among Oghalai’s many happy patients. He can pick up subtle conversations, even in field training sessions and a busy emergency room. When he spends time at the family’s property near San Luis Obispo, every word — or moo — that’s said, he can pick up. Before he had the procedure, his youngest son learned to speak louder. Now, when Noah turns up the volume, his dad can say, “It’s ok, buddy. You don’t have to yell.”

— Candace Pearson