The available vaccines have proved to be safe and effective. The task is to disseminate updated, credible information.

By Sarah Nightingale

When it comes to getting a COVID-19 jab, Los Angeles resident Bobbye Gooden is more worried about long lines at the clinic than the vaccine itself.

“I’m 70 years old, so I don’t want to be standing in line at the doctor’s office or waiting for hours in a car at Dodger Stadium,” said Gooden, a retired respiratory care practitioner who also worked as a project manager for a domestic violence response team. “I do plan to get the vaccine, but I’m not in a rush.”

It’s a sentiment not everyone shares. More than a quarter (27%) of Americans remain hesitant about getting the shot, saying they “probably or definitely would not get a COVID-19 vaccine even if it were available for free and deemed safe by scientists,” according to Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, published in December 2020. That number is higher among Black adults, with 35% saying they “definitely or probably would not get vaccinated.”

There are several reasons people may not want to get a COVID-19 vaccine, said Edward Jones-López, MD, MS, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. The reasons include support of the anti-vaccine movement, worries about side effects, a lack of trust in the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness, and fears that development of the vaccines was rushed. For many Black Americans, those fears are compounded by a long-standing mistrust of the U.S. healthcare system.

Gooden, who describes herself as multi-racial, with African American, Native American and Irish ancestors, said she understands their reluctance.

“When I was growing up, I remember my parents talking about the Tuskegee experiments,” Gooden said. “So yes, I understand people’s concerns—the fact that they don’t want to be treated like guinea pigs.”

The Tuskegee Experiment is probably the best known example of research abuses in the United States. Officially named “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” the decades-long experiment was started in the 1930s by the U.S. Public Health Service to investigate the progression of syphilis among Black men—except the 600 research subjects weren’t told the truth about the purpose of the experiment or their health status.

“Stories of these abuses have been passed down from generation to generation, so there is real fear about the healthcare system and physicians among minorities, and I think rightly so,” said Jones-López, who is one of dozens of USC physicians working to understand and address medical inequalities in Los Angeles County.

Myriad other research abuses have been documented in African Americans and minority populations—including Latinos, Native Americans, mentally ill patients, and prisoners. Considering that history, it’s not surprising that many are wary about participating in clinical trials or receiving an injection. That’s a concern, Jones-López said, because it may exclude minorities from benefiting from ground-breaking new drugs or receiving life-saving vaccines.

“It is worth noting that current research studies are much safer and more ethical as a result of a multitude of improvements and checks that have been implemented over the last 50 years,” he said.

People of color are experiencing significantly higher rates of coronavirus infections and deaths than white Americans, according to federal, state and county data. APM’s Research Lab reports that Black, Indigenous, and Latino Americans are at least 2.7 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white Americans, a finding that is underpinned by inequalities in the way minorities live, work, and access transportation and health care. Despite these figures, just 27% of Black adults and 36% of Hispanic adults say they will definitely get the vaccine, compared with 46% of white adults, according to Kaiser Family Foundation.

“There continues to be real evidence of health disparities in Black and Brown populations,” said Jehni Robinson, MD, professor of clinical family medicine and chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Keck School. “Coronavirus is one indicator, but there are many others, including more deaths from heart disease and cancer, and more amputations from diabetes.”

Such disparities can cause suspicion, Robinson said. “And when people are suspicious, they often turn inward, seeking advice from family and friends, which results in an echo chamber situation.”

Robinson said there are several ways to build trust in minority communities, ranging from long-term efforts to train more physicians and scientists of color to immediate actions like community outreach.

“I try to build personal relationships with patients and their families, but this takes time and isn’t easy to do in one visit,” Robinson said. “When it comes to vaccine-hesitant populations, we can’t wait for them to come to us: We have to reach out to people through churches and community groups.”

Robinson said community conversations can steer people to scientifically sound resources, such as the L.A. County Department of Public Health, which has information about COVID-19 and the vaccines in a variety of languages.

“I like to tell people that if you want a good recipe, you ask a chef. And if you want health information, you need to go to a source that is backed with reliable science,” she said.

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, PhD, MPH, a professor of preventive medicine, associate dean for community initiatives and a member of the Pandemic Research Center at the Keck School of Medicine, is developing public health messaging to dispel myths and reduce fear surrounding the vaccines, especially among communities of color.

About half of the Black adults who say they probably or definitely won’t get a vaccine attribute their hesitancy to mistrust of vaccines in general, or concern that they could get COVID-19 from the vaccine, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Baezconde-Garbanati’s community-based research in Los Angeles highlights additional fears among people of color, including worries the vaccine could cause infertility in women, concerns the syringes containing the vaccine may also include an injectable microchip or tracking device, or fears the vaccine was rushed. All of these, she said, are “completely false.”

About 3% of Americans had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by mid-January. But in the 16 states that have released data by race, white adults were being vaccinated at significantly higher rates than Black adults — two to three times higher in many cases, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis. A similar analysis of data from 14 states by CNN found twice as many white Americans had received the vaccine than their Black and Latino counterparts.

Pfizer and Moderna, which make the two vaccines that have been approved by the FDA so far, announced in November they had developed and tested vaccines that were around 95% effective in preventing COVID-19. The first doses were given in December. Given that a year prior no one knew about the novel coronavirus, the rate of vaccine development was unprecedented.

“The vaccine development was expedited but not rushed,” Baezconde-Garbanati said. “All of the proper procedures were followed and no steps were skipped, but advances in the science of vaccine development, as well as the fact researchers from all over the world were working on this, accelerated the process.”

To tackle these misconceptions, Baezconde-Garbanati and her colleagues are using the acronym SAFE:

- Safe—the risks and side effects are small compared with the benefits.

- Available—based on risk group.

- Free—although some providers may charge an administration cost.

- Effective—both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are approximately 95% effective in preventing COVID-19 disease when administered as directed (which requires two doses).

Robinson worries that if people of color, who have already been hardest hit by the pandemic, opt not to get vaccinated, the gap will widen.

“My projection is that if a significant number of people of color decline the vaccine, those populations will become even more at risk because we know the virus spreads within families and communities,” Robinson said.

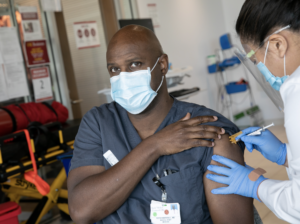

Jones-López, who has treated hundreds of patients and describes the healthcare workers he serves with as “exhausted,” made a plea for all healthy people to get the vaccine once it is available. As frontline medical practitioners, Robinson and Jones-López have both received the vaccine.

“If we don’t reach a vaccination rate of 70-80%, we won’t reach herd immunity needed to offer protection to the whole population, including groups that cannot get the vaccine immediately because of insufficient safety and efficacy data, such as children, people with severe allergies and those with certain medical conditions,” Jones-López said. “That’s why we need all healthy individuals to be on board with this.”