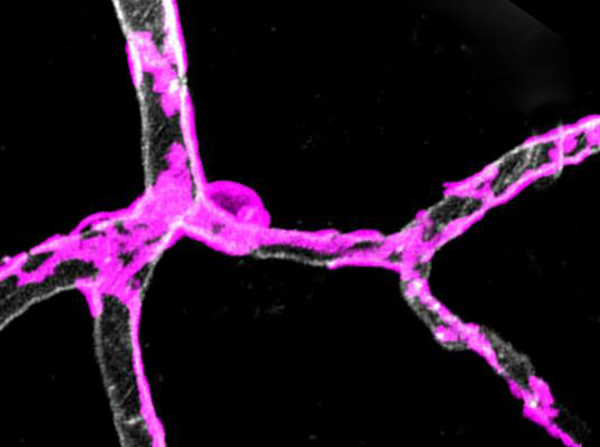

Pericytes, or gatekeeper cells, are wrapped around capillaries in the cortex of a mouse brain. (Amy Nelson/Keck School of Medicine of USC)

Abnormality with special cells that wrap around blood vessels in the brain leads to neuron deterioration, possibly affecting the development of Alzheimer’s disease, a USC-led study reveals.

“Gatekeeper cells” called pericytes surround blood vessels, contracting and dilating to control blood flow to active parts of the brain.

“Pericyte degeneration may be ground zero for neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, ALS and possibly others,” said Berislav Zlokovic, senior author of the study and director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “A glitch with gatekeeper cells that surround capillaries may restrict blood and oxygen supply to active areas of the brain, gradually causing neuron loss that might have important implications for Alzheimer’s disease.”

Published on Jan. 30 in Nature Neuroscience, this was the first study to use a pericyte-deficient mouse model to test how blood flow is regulated in the brain. The goal was to identify whether pericytes could be an important new therapeutic target for treating neuron deterioration.

“Vascular problems increase the risk of cognitive impairment in many types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease,” said Kassandra Kisler, co-first author and a research associate at the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute. “Pericytes play an important part in keeping your brain healthy.”

A closer look at the mouse models

Pericyte dysfunction suffocates the brain, leading to metabolic stress, accelerated neuronal damage and neuron loss, said Zlokovic, holder of the Mary Hayley and Selim Zilkha Chair in Alzheimer’s Disease Research.

To test the theory, researchers stimulated the hind limb of young mice deficient in gatekeeper cells and monitored the global and individual responses of brain capillaries, the smallest blood vessels in the brain. The global cerebral blood flow response to an electric stimulus was reduced by about 30 percent compared to normal mice, denoting a weakened system.

Relative to the control group, the capillaries of pericyte-deficient mice took 6.5 seconds longer to dilate. Slower capillary widening and a slower flow of red blood cells carrying oxygen through capillaries means it takes longer for the brain to get its fuel.

As the mice turned 6 to 8 months old, global cerebral blood flow responses to stimuli progressively worsened. Blood flow responses for the experimental group were 58 percent lower than that of their age-matched peers. In short, with age, the brain’s malfunctioning vascular system exponentially worsens.

“We now understand the function of blood vessel gatekeeper cells is to ensure adequate oxygen and energy supply to brain cells,” said Amy Nelson, co-first author and a postdoctoral scholar at the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute. “Prior to our study, scientists knew patients with Alzheimer’s disease, ALS and other neurodegenerative disorders experience changes to the blood flow and oxygen being supplied to the brain and that pericytes die. Our study adds a new piece of information: Loss of these gatekeeper cells leads to impaired blood flow and insufficient oxygen delivery to the brain. The big mystery now is: What kills pericytes in Alzheimer’s disease?”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the American Heart Association.

Scientists at the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute, the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute at the Keck School of Medicine and other collaborators are already working to further this line of research, scanning the brains of people who are genetically at risk for Alzheimer’s. They are also collecting cerebral spinal fluid and blood for analysis of vascular damage, including injury to pericytes.

By Zen Vuong