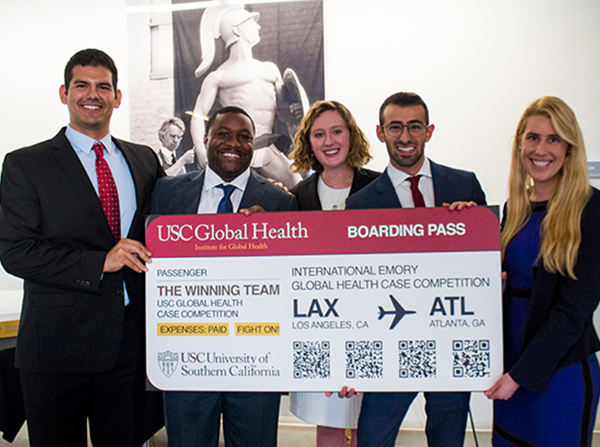

Members of the winning team are students at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and USC Sol Price School of Public Policy. From left are Julian Cernuda, Brantynn Washington, Cristina Gago, Hrant Gevorgian and Ashley Millhouse. (Photo/Larissa Puro)

Students from across USC’s campuses spent a week strategizing ways to improve Nicaragua’s surgical infrastructure as part of the sixth annual USC Global Health Case Competition.

The competition, held Feb. 14 for all USC students and hosted by the Institute for Global Health, partnered with medical charity Operation Smile and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles to develop a case challenge based on the organization’s experience providing surgical care in more than 60 countries worldwide.

The Institute for Global Health collaborates with an organization every year to provide competitors with diverse, real-world challenges in various countries. Previous partners included the American Cancer Society; TOMS; World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and International Medical Corps.

Cross-campus collaboration

Approximately 50 students participated, in multidisciplinary teams, from seven USC schools. The case presented a classic global health quandary — how to maximize meager time, money and support to save as many lives as possible in low-resource countries — but in a less familiar context: global surgery.

“The needs in global surgery have been largely unmet so finding research related to that [/fusion_builder_column]

Millhouse and two of her teammates, biology and MPH progressive degree undergraduate Cristina Gago and MPH classmate Hrant Gevorgian, had competed together in last year’s competition — and made it to the final round.

“We did the case competition last year and thought it was an amazing, hands-on opportunity for us to really learn about global health companies and organizations, and have this fast-paced intensity to identify new strengths or areas of opportunity,” Millhouse said.

This year, their team included Master of Public Administration candidates Julian Cernuda and Brantynn Washington. After advancing once again to the final round, they won. The team will travel to Atlanta to represent USC at the International Emory University Global Health Case Competition on March 25.

Global surgery partnership

Operation Smile has been providing cleft lip and palate surgeries worldwide since William and Kathy Magee founded the organization in 1982. Their son, William Magee III, MD, DDS, is an assistant professor of clinical surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC as well as the director of the International Research Program in the Department of Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Magee III presented a lecture during the competition about innovations and challenges of the emerging global surgery field and focused on the Global Surgery Partnership, a novel collaboration between the Keck School, CHLA and Operation Smile.

The institutions joined together in 2011 to bridge academia and charitable surgery through education, research and service. The partnership’s main projects include the International Family Study and Barriers to Care Study, which integrates USC students, plastic surgery residents and faculty into the etiology research and indexing of cleft, as well as defining the barriers to accessing surgical care in low-resource settings.

Two-thirds of the world’s population lacks access to safe surgery, according to The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery in 2015. The Disease Control Priorities Network reports 11 percent of the total global burden of disease could be treated with surgery, but currently only six percent of surgical procedures performed each year take place where people need it most — in Nicaragua, for example.

As mock consultants for Operation Smile, the competitors were tasked with developing sustainable operating room systems in Nicaragua. The teams pitched ideas to faculty judges in 15-minute presentations.

Classroom skills translate to real-world solutions

Millhouse’s team designed the program Sonríe de Nuevo, which means “Smile Again,” based on Operation Smile’s “diagonal approach” to achieving safe, accessible surgical care through training, self-sustaining revenue, research, partnership, infrastructure and capacity-building.

Identifying existing partners and initiatives locally in Nicaragua, the students presented collaboration ideas to make the most of existing resources and cutting-edge innovation. They proposed transforming plentiful and easily transported cargo containers into operating rooms, capable of being connected into a fully functional hospital. The team also proposed raising salaries for health care workers to avoid “brain drain,” in which skilled workers leave their countries to seek higher wages.

Applying each teammate’s individual skills and knowledge was key to the team’s successful presentation.

“I think what’s so exciting about this competition is that it brings people from all different disciplines together and it makes us think about things that I wouldn’t think of on my own — from the policy standpoint, and bureaucracy and government, as well as advocacy,” Gago said.

From the public health perspective, core courses in global health and leadership prepared the students to be culturally competent and how to conduct work on a global scale, according to Gevorgian.

Finally, the team’s strength in public administration helped convey their points.

“It’s great to have a fantastic idea, but at the end of the day you have to make it translatable to people on the ground,” Cernuda said.

Magee III praised the competition as an important educational exercise. “Leadership and problem-solving,” he said, “you only get good at it by doing it.”

He called on students to serve — everyone, anywhere and however they can, a message Washington said resonated with him as he prepares for his team’s presentation on the international level.

“You can start with experiences that are very simple. You don’t have to change the world,” Magee III said. “But they will start to teach you about ways in which you can be innovative and think outside the box.”

— Larissa Puro