Prof. Steve Kay’s latest honor comes about a year after he was elected to the Royal Society of London, and 12 years after his election to the National Academy of Sciences in 2008. (Photo/Max Gerber)

Flowers seem to know, instinctively, when to open and close — when the light is just right, and when their insect pollinators are most likely to come calling.

Human beings also are regulated by biological clocks: There’s an optimal time for them to eat, and to go to sleep. Deviate too much from these natural rhythms, and their health could be adversely affected.

Steve Kay, PhD, Provost Professor of Neurology, Biomedical Engineering and Biological Sciences, and Director of Convergent Biosciences at the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, as well as Director of the Keck School of Medicine’s MESH Academy, has studied the circadian rhythms in plants for years, looking for commonalities that could improve human health. On Monday, the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms (SRBR) honored him with the 2020 Director’s Award in Research at the group’s once-every-two-years national meeting.

“We are extremely proud of Dr. Kay, and congratulate him on this honor,” said Laura Mosqueda, MD, Dean of the Keck School. “This award represents years’ worth of hard work, curiosity and dedication. Studying the genes of a mustard plant for clues on how to treat some of our most confounding diseases is a great example of the innovation we love to see at the Keck School.”

The honor comes just over a year after Kay was elected as a fellow to the Royal Society of London; he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2008.

“There’s a gratitude and humility you feel when your colleagues — who are your toughest critics — single you out for recognition,” Kay said. “You kind of end up with this sense of just how lucky you’ve been to work with amazing people.”

The SRBR was established in 1986, and now includes some 700 members, including PhDs and MDs, from different disciplines. Their varied interests include the study of sleep, of diet, and finding new treatments for persistent diseases. One commonality is circadian rhythms — “how organisms control the timing of various internal biological events and how they take in cues for the environment (such as light and food),” according to the SRBR’s page on the subject.

Kay says the SRBR has recognized in recent years that “this field of circadian medicine has really become very prominent. We’re interested in what time of day drugs should be given to patients, to get additional benefit or better safety. Lots of studies have shown that, in chronic shift work, workers like nurses who are exposed to nighttime light, they tend to be susceptible to a lot of chronic disease that are probably linked to their circadian clock. Not least of which is diabetes and obesity, but also breast cancer.”

Arabidopsis plants growing in Prof. Kay’s lab in the basement of the Norris Cancer Center on USC’s Health Sciences Campus. (Photo/USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience)

The study of circadian rhythms has brought the SRBR to other conclusions, like: Eating right before bed is worse than during the day, when the body is more active; don’t overstimulate with electronic devices late at night; and a stance many people can relate to: Daylight savings time, and its twice-annual disruption to our sleep, should go away.

The British-born Kay, who earned his PhD from the University of Bristol, was working as a plant biologist at the Rockefeller University in Manhattan when he made an important discovery: Within a small, flowering mustard plant called an Arabidopsis, specific genes were regulated on a 24-hour clock. The Arabidopsis makes an excellent model for scientists to work with, because it’s easy to grow in the lab, and it goes from seed to flower to harvesting seed again in only about six weeks. Kay and his team have containers of them growing under LED lights in his lab, which is affiliated with USC’s Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and is located in its basement. “It’s like an underground greenhouse,” he said.

Like all plants and animals, the Arabidopsis contains cryptochromes, a sort of clock protein. It “senses light intensity, so that plants can make growth decisions based on measuring the light environment,” Kay said. “Plants are a lot more clever than we think they are.”

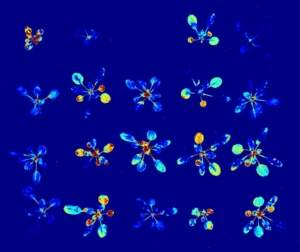

A pseudocolored image of clock gene-driven bioluminescence from transgenic plants expressing firefly luciferase under circadian control. (Photo/USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience)

He added that cryptochromes could have an application in treating certain cancers, including glioblastoma, a fast-growing brain tumor. The SRBR committee chose Kay for the Director’s Award in Research for “establishing Arabidopsis as a circadian model organism and identifying the core set of clock genes in plants.”

“For me, this all started 25 years ago with a little mustard plant, where I accidentally stumbled on the fact that it had a 24-hour clock controlling the expression of some of its genes,” Kay said. “Fast-forward 25 years later, we’re working on cancer targets, we’re working on diabetes, drug targets. We’re working on the clock in the brain and how it regulates the sleep-wave cycle. I never could have possibly imagined that.”

— by Landon Hall

(Congratulate Dr. Kay by sending him an email!)