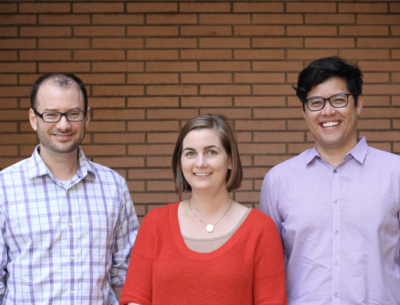

From left, Dion Dickman, Megan McCain and Justin Ichida collaborate to find new approaches to treating ALS, with support from a Broad Innovation Award. (Photo by Cristy Lytal)

(Originally posted at USC Stem Cell)

By Cristy Lytal

Now that Justin Ichida and Dion Dickman are both tenured professors at USC, they no longer have to worry about who was the coolest kid in their elementary schools back in Honolulu.

But just for the record, it was Ichida.

As a third-generation Hawaiian, Ichida fit right in. His background was similar to many on the islands, with some ancestors who were Native Hawaiian, and great grandparents who left Japan to work the sugar cane plantations. His mother was one of four children who grew up in a two-bedroom house without hot water on Kauai, and she later became a successful realtor on Oahu and married Ichida’s father, an attorney.

“He did a lot of litigation, crazy stuff,” said Ichida. “He did cases where a boulder came down from the mountain and just smashed somebody’s house and killed somebody. There was a big case with Chevron where their pipes were leaking gas into the underground layer of the island and polluting the surrounding areas—a lot of things having to do with unique instances that occur in that island environment.”

Meanwhile, as the son of white hippie parents, Dickman stood out as a more of an oddball on the islands. Dickman’s father appeared on the original poster for the Woodstock film, and he first moved to Hawaii to grow a cash crop that has since become legal in certain states. He and Dickman’s mother lived commune-style in a shack without electricity, buying one 50-pound bag of rice each month for food. Dickman’s father later parlayed his agricultural expertise into a PhD in plant pathology, became a professor, and saved the state’s papaya crop from a major disease outbreak.

“There were not that many white people that lived there, raised kids and all that, at least when I was growing up,” said Dickman. “It was mostly Native Hawaiian, Asian, or Samoan. It wasn’t like a racist term, but even the teachers would call me ‘Haole Boy.’ So Justin and I probably crossed paths somewhere here or there, but he was the cool kid, and I was that weird ‘Haole Boy’ that he probably didn’t like too much growing up.”

Even so, Dickman and Ichida were probably more alike than different, and they both saw the world around them through the eyes of future scientists.

Ichida got hooked on science in seventh grade when he read Jurassic Park, and gained further inspiration from his high school biology teacher at the ‘Iolani School.

“Jurassic Park is this story about how they resurrected the dinosaurs by using chemical tricks on their DNA, and I just thought that was really neat to be able to manipulate biology like that,” he said.

Dickman made his first acquaintance with science in his father’s graduate school lab, as well as through the amazing diversity of life on the Hawaiian islands—from the giant orange-and-black centipedes to the bright green geckos. After attending Honolulu’s Hokulani Elementary School for a few years, Dickman moved to Nebraska, where his father had secured a faculty position. When Dickman was in high school, he joined a virology lab at the University of Nebraska and commissioned a related tattoo.

“I got this old textbook for like $5, used, at the university bookstore,” he said. “And there was a chapter about phages, which are bacterial viruses. And the way a phage looks is really cool. It looks like a rocket ship from an alien. I cut it out and brought it to a tattoo guy.”

Ichida majored in microbiology and molecular genetics as undergraduate at UCLA, and maintained his cool factor by performing in hula shows and even hosting a lu’au complete with a roast pig. Dickman earned his bachelor’s degree in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Washington University in St. Louis, and worked in a neuroscience lab during his freshman year. By the time Dickman entered the PhD program in Biological and Biomedical Sciences at Harvard University, he had also become pretty cool. Then one year later, Ichida joined the same program.

“Dion used to the be the coolest guy from Hawaii in our PhD program until I showed up,” said Ichida.

“While Justin may have been the coolest, I like to think that I’m the best looking, indeed to this day,” said Dickman. “But we had similar friends, and we would hang out. We have similar personalities, too. For scientists, I think we’re pretty cool.”

Justin Ichida and the band Holding Room playing a 2005 benefit concert at P.A.’s Lounge to benefit Hurricane Katrina relief (Photo courtesy of Justin Ichida)

In graduate school, Ichida studied the genetics of the “primordial soup” as a PhD candidate, and moved on to the genetics of humans as a postdoctoral trainee, also at Harvard University. He invented simpler ways to turn adult skin cells into stem cells, and later to directly reprogram skin cells into motor nerve cells. He also maintained his cool factor as a member of two rock bands: Holding Room and Maniatis, which was named after a famous molecular biologist.

Even though Dickman was pretty cool, he never made it to one of Ichida’s concerts. Instead, he spent his PhD years searching for genes that altered the function of synapses, which are the intersections between nerve cells, in fruit flies. For his postdoctoral training, he joined a different fly laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco, where he studied synapses’ ability to change, which is known as “plasticity.”

In 2012, Dickman earned his first faculty position, and is now an Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. One year later, Ichida followed in his footsteps, and is now the John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Foundation Associate Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

“I still remember when Justin was interviewing and being recruited to USC, and stem cell department chair Andy McMahon somehow knew we were friends,” said Dickman. “He emailed me and was like, ‘Hey, we’ve got this guy Justin. He looks great. Let’s try to recruit him. I’m going to need you to be the point man.’ And I was like, ‘Oh man, I could tell you all these stories about Justin that would probably change your perspective on him!’ But I was thinking that I’d love to have Justin here as a good friend and colleague.”

At USC, Ichida’s laboratory uses nerve cells, derived from patient skin cells, to understand and find treatments for neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS and certain forms of dementia.

Dickman’s laboratory relies on flies to study how nerve cells balance excitation and inhibition at their synapses—contributing to either healthy neurological function or disease.

In 2016, Dickman, Ichida and USC biomedical engineer Megan McCain won a Broad Innovation Award to collaborate on a new approach for studying ALS. Among other things, the disease damages what are known as neuromuscular junctions—the space where motor nerve cells release the chemical signals that instruct muscle cells to contract. To better understand this process, the scientists used skin or blood cells from patients with ALS to create neuromuscular junctions on a gelatin scaffold, called a “chip.” They then performed tests on these patient-specific neuromuscular junctions to understand which therapies might halt or reverse damage from the disease.

More recently, Ichida and Dickman began a new collaboration related to ALS, with funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In this project, the team is exploring how ALS changes the activity of synapses, and how to strengthen and protect these synapses using a specific drug-like molecule. To study this, they will expose a large number of flies to this drug-like molecule, and then measure the function of their synapses using electrophysiology.

“We think that this drug-like molecule partly works through modulating synaptic plasticity, which is actually Dion’s specialty,” said Ichida. “So our collaboration is going to get even cooler.”

Dickman added, “It’s fun working with someone you’re friends with and that you respect. It’s not just a professional colleague thing. I knew Justin when he looked much less mature and professorial, so there’s always that history. I mean, clearly, I’ve aged a little bit as well, but I’ve retained my good looks, I like to think.”

In April 2020, Dickman and Ichida were both awarded tenure at USC. With the tenure decision no longer looming, Dickman and Ichida look forward to feting their accomplishment.

“COVID shut things down for a while, but I’m orchestrating a tenure party for Justin and me—and 34 of our closest friends,” said Dickman.

“We’re going to celebrate together,” said Ichida.