Scientists from the Keck School of Medicine of USC identify key cells involved in the process of cartilage regeneration in lizards—a discovery that could offer insights into novel approaches to treating osteoarthritis.

By Hope Hamashige

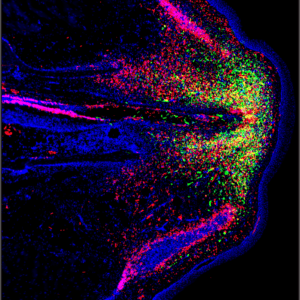

A team of researchers from the Keck School of Medicine of USC have published the first detailed description of the interplay between two cell types that allow lizards to regenerate their tails. This research, funded by the National Institutes of Health and published on August 10 in Nature Communications, focused on lizards’ unusual ability to rebuild cartilage, which replaces bone as the main structural tissue in regenerated tails after tail loss.

The discovery could provide insight for researchers studying how to rebuild cartilage damaged by osteoarthritis in humans, a degenerative and debilitating disease that affects about 32.5 million adults in the United States, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There is currently no cure for osteoarthritis.

“Lizards are kind of magical in their ability to regenerate cartilage because they can regenerate large amounts of cartilage and it doesn’t transition to bone,” said the study’s corresponding author Thomas Lozito, assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery and stem cell biology and regenerative medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Lizards are among the only higher vertebrates capable of regenerating cartilage that does not ossify and are the closest relatives to mammals that can regenerate an appendage with multiple tissue types, including cartilage. Humans, by contrast, cannot repair cartilage that has been damaged once they reach adulthood. (…Read More)