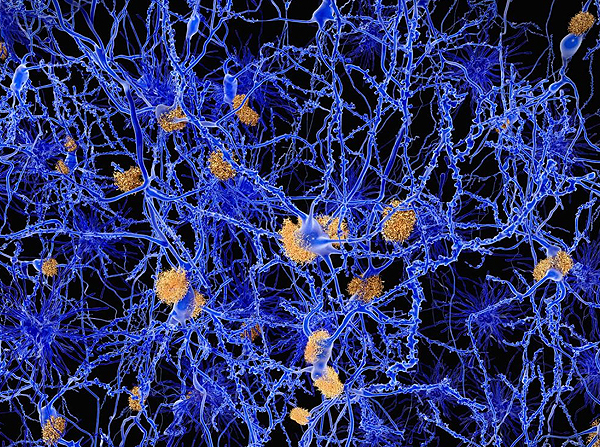

USC researchers say toxic, sticky proteins called amyloid plaques are part of Alzheimer’s disease, the earliest precursor before symptoms arise. (Illustration/iStock)

Clusters of a sticky protein — amyloid plaque — found in the brain signal mental decline years before symptoms appear, a new study finds

Older adults with elevated levels of brain-clogging plaques — but otherwise normal cognition —experience faster mental decline suggestive of Alzheimer’s disease, according to a new study led by the Keck School of Medicine of USC that looked at 10 years of data.

Just about all researchers see amyloid plaques as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s.

However, this study presents the toxic, sticky protein as part of the disease — the earliest precursor before symptoms arise.

“To have the greatest impact on the disease, we need to intervene against amyloid, the basic molecular cause, as early as possible,” said Paul Aisen, senior author of the study and director of the USC Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute (ATRI) at the Keck School of Medicine. “This study is a significant step toward the idea that elevated amyloid levels are an early stage of Alzheimer’s, an appropriate stage for anti-amyloid therapy.”

Notably, the incubation period with elevated amyloid plaques — the asymptomatic stage — can last longer than the dementia stage.

“This study is trying to support the concept that the disease starts before symptoms, which lays the groundwork for conducting early interventions,” said Michael Donohue, lead author of the study and an associate professor of neurology at USC ATRI.

The researchers likened amyloid plaque in the brain to cholesterol in the blood. Both are warning signs with few outward manifestations until a catastrophic event occurs. Treating the symptoms can fend off the resulting malady — Alzheimer’s or a heart attack — the effects of which may be irreversible and too late to treat.

We’ve learned that intervening before the heart attack is a much more powerful approach to treating the problem.

-Michael Donohue

“We’ve learned that intervening before the heart attack is a much more powerful approach to treating the problem,” Donohue said.

Aisen, Donohue and others hope that removing amyloid at the preclinical stage will slow the onset of Alzheimer’s or even stop it.

The amyloid problem

One in three people over 65 have elevated amyloid in the brain, Aisen noted, and the study indicates that most people with elevated amyloid will progress to symptomatic Alzheimer’s within 10 years.

If Alzheimer’s prevalence estimates were to include this “preclinical stage” before symptoms arise, the number of those affected would more than double from the current estimate of 5.4 million Americans, the study stated.

Published in The Journal of the American Medical Association on June 13, the study uses 10 years of data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, an exploration of the biomarkers that presage Alzheimer’s. USC ATRI is the coordinating center of this North American investigation. Aisen co-directs its clinical core.

USC plays a leading role in the only two anti-amyloid studies focused on the early, preclinical stage of sporadic Alzheimer’s: The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study (the A4 Study) and the EARLY Trial, Aisen said.

“We need more studies looking at people before they have Alzheimer’s symptoms,” Aisen said. “The reason many promising drug treatments have failed to date is because they intervened at the end-stage of the disease when it’s too late. The time to intervene is when the brain is still functioning well — when people are asymptomatic.”

Although elevated amyloid is associated with subsequent cognitive decline, the study did not prove a causal relationship.

For years, researchers have acknowledged age is the biggest risk factor when it comes to Alzheimer’s. For more than 90 percent of people with Alzheimer’s, symptoms do not appear until after age 60, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2014, about 46 million adults living in the United States — 15 percent of the population — were 65 or older. By 2050, that number is expected to expand to 88 million or 22 percent of the population.

The tipping point

Researchers measured amyloid levels in 445 cognitively normal people in the United States and Canada via cerebrospinal fluid taps or positron emission tomography (PET) scans: 242 had normal amyloid levels and 202 had elevated amyloid levels. Cognitive tests were performed on the participants, who had an average age of 74.

Although the observation period lasted 10 years, each participant, on average, was observed for three years. The maximum follow-up was 10 years.

The elevated amyloid group was older and less educated. Additionally, a larger proportion of this group carried at least one copy of the ApoE4 gene, which increases the odds that someone will develop Alzheimer’s.

Based on global cognition scores, at the four-year mark, 32 percent of people with elevated amyloid had developed symptoms consistent with the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. In comparison, only 15 percent of participants with normal amyloid showed a substantial decline in cognition.

Analyzing a smaller sample size at year 10, researchers noted that 88 percent of people with elevated amyloid were projected to show significant mental decline based on global cognitive tests. Comparatively, just 29 percent of people with normal amyloid showed cognitive decline.

Alzheimer’s disease research worldwide

Alzheimer’s was recently a disease that could be diagnosed only after death with an autopsy.

Aisen and the researchers at USC ATRI have developed ways to identify early signs of Alzheimer’s by creating a set of cognitive tests called the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite. This battery of tests and variations of it are widely used to detect Alzheimer’s before dementia symptoms emerge, Aisen said.

“Our outcome measures are becoming the standard for early Alzheimer’s disease intervention studies,” Aisen said. “Drug companies will not invest in early intervention studies without a regulatory pathway forward. ATRI and USC are building a framework for drug development in Alzheimer’s disease.”

As a research institution devoted to promoting health across the life span, USC has more than 70 researchers dedicated to the prevention, treatment and potential cure of Alzheimer’s disease.

Reisa Sperling at Harvard Medical School, Ronald Petersen at the Mayo Clinic, Chung-Kai Sun at USC ATRI and Michael Weiner at the University of California, San Francisco also contributed to this study.