Research funded by the grant will capitalize on the development of biomarkers and advanced imaging by scientists at the Keck School of Medicine of USC to launch studies tracking changes in the blood-brain barrier, neurovascular function and cognition.

By Hope Hamashige

The National Institute on Aging, a division of the National Institutes of Health, awarded Berislav Zlokovic, MD, PhD, director of the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute, and Arthur W. Toga, PhD, director of the USC Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (Stevens INI), $16.1 million to continue research on the role that blood vessel dysfunction plays in the development of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“There is increasing evidence that neurovasculature has a major role in early cognitive decline,” said Zlokovic, chair and professor of physiology and neurosciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. “This grant allows us to continue important research on how changes in the blood-brain barrier and blood flow interact with amyloid-beta and tau pathology to trigger structural and functional changes in the brain leading to cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease.”

More than 30 years ago, Zlokovic was among the first to propose that flaws in the blood-brain barrier, which keeps harmful substances in the blood from moving into brain tissue, could be the early, underlying cause of most cognitive disorders, rather than the accumulation of amyloid beta plaque, which had long been the focus of Alzheimer’s research. With this award, he and his colleagues can further test this so-called neurovascular hypothesis.

“This work will build on our earlier work, which has shown that people can progress to mild cognitive impairment, independent of amyloid beta and tau if the blood-brain barrier is damaged,” said Zlokovic.

Documenting Alzheimer’s disease progression

The funding will allow the team of researchers to launch longitudinal studies comparing the progress of more than 400 people who have a genetic variant putting them at high risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease — known as apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4) — with more than 450 people with APOE3, a different variant which puts them at lower risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

About 75% of the participants will be cognitively unimpaired at the start of the study and about 25% will have only mild impairment. The researchers will follow them for five years, tracking changes in the blood-brain barrier, blood flow and the brain’s structure and function while monitoring participants for cognitive impairment, using neuroimaging and molecular biomarkers indicating blood vessel dysfunction, which were developed by Zlokovic, and advanced brain imaging technology developed by Toga.

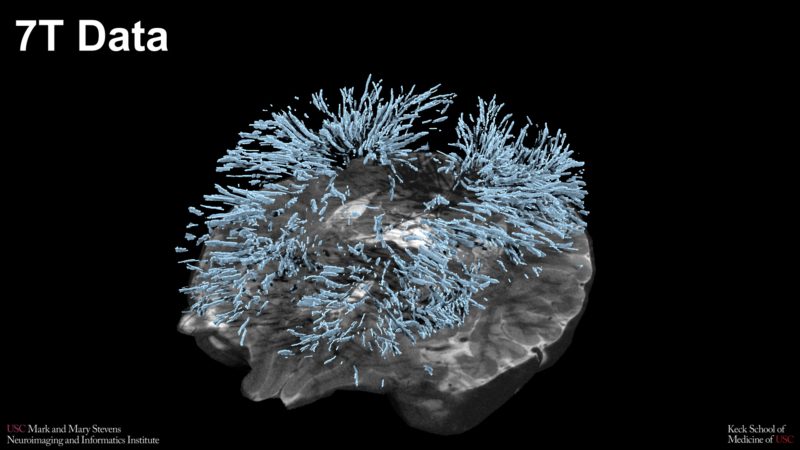

Perivascular spaces in the brain highlighted using data from the Stevens INI’s ultra-high field 7T MRI scanner Credit: Stevens INI

“Using our ultra-high field 7T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner has transformed our understanding of how fluid-filled regions in the brain — perivascular spaces — impact brain health. Here at the Stevens INI, we have successfully used this advanced imaging to facilitate breakthroughs, including the central role that perivascular space plays in brain changes associated with aging, including neurodegenerative disorders,” said Toga, Provost Professor of Ophthalmology, Neurology, Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences, Radiology and Engineering at the Keck School of Medicine. “Our imaging capabilities have allowed us to create a multimodal assessment of the role of neurovasculature in cognitive decline, a comprehensive research program on perivascular spaces, and numerous close-up investigations of how fluids travel through the brain, including via the blood-brain barrier. I’m thrilled to have received this funding to continue our work in partnership with Dr. Zlokovic.”

Arthur W. Toga, PhD, director, Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute Director. (Photo INI)

Researchers hope the work will lead to a better understanding of the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease and the identification of the best interventions for different stages of the disease.

Testing treatments in the lab

Simultaneously, the team will conduct complementary laboratory research using mice that have been genetically altered to carry human APOE gene variants to help document changes in the brain that lead to cognitive decline and to test a potential treatment.

The treatment is an experimental neuroprotective enzyme co-developed by Zlokovic’s team, in collaboration with John Griffin, PhD, from the Scripps Research Institute, called 3K3A-APC, an engineered form of human activated protein C. Researchers will test it in the altered mice to see if it can protect the integrity of the blood-brain barrier and prevent cognitive decline. In addition they hope to examine whether this type of intervention is effective at the earliest signs of vascular dysfunction or at later stages of disease in mouse models that also have amyloid beta and tau. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) recently awarded funding for a pivotal Phase 3 clinical trial of 3K3A-APC in stroke patients, led by Patrick Lyden, MD, professor of physiology and neuroscience at the Zilkha Neurogenetic Institute.

“We hope that the results of this research will eventually lead us to new treatments for people with the APOE4 gene,” said Zlokovic.

Turning biomarkers into a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease

Zlokovic added that they continue to improve on key molecular biomarkers, and he hopes eventually to discover biomarkers detectible in blood, which would make the process of identifying people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease simpler and more accessible.

“We have been pursuing several avenues of research that all complement one another,” said Zlokovic. “We believe that this research will contribute to important new findings about the pathogenesis of cognitive decline and will also lead to development of important new therapies for cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.”