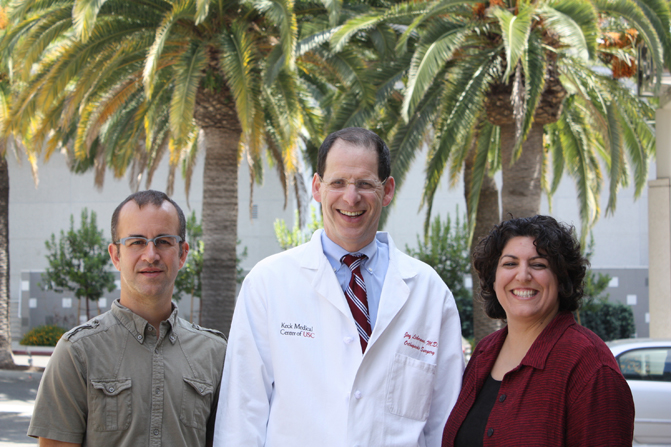

One winning team brings together Jay R. Lieberman (center), a clinical orthopaedic surgeon and chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, and two researchers within the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research — Gage Crump and Francesca Mariani.

As chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, Jay R. Lieberman regularly sees patients with bone defects too severe to heal. This unmet clinical need inspired him to team up with two stem cell biologists, Gage Crump and Francesca Mariani, to find new solutions.

“I was treating patients with large bone defects associated with revision total hip and knee replacement,” said Lieberman. “Another group that we have seen more recently in the past decade are soldiers, who unfortunately sustained high energy injuries from explosive devices or gunshot wounds, where they have lost a lot of soft tissue and bone. And our hope with our research is to develop solutions for these problems.”

Lieberman, Crump and Mariani kicked off their official collaboration in 2013, when they received a $400,000 pilot grant from the Regenerative Medicine Initiative, funded by the Keck School’s dean. Supported by these funds, the team focused on potential ways to repair human bones through lessons learned from two not-so-distant relatives: zebrafish and mice.

“A great benefit of the Regenerative Medicine Initiative is that basic biologists are encouraged to work with clinicians to understand the most pressing challenges that need to be overcome in order to augment bone healing and bone regeneration in people,” said Crump, a principal investigator at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center for Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at USC.

In its early stages, the project also attracted considerable support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In 2013, Mariani received an NIH Exploratory/Development Grant Award, called an R21, to develop a new bone regeneration model in mice. In 2014, Crump leveraged this momentum to secure an additional NIH R21 grant, advancing these investigations in zebrafish.

“As an adult, a zebrafish can repair 20 percent of a missing heart, a fully severed spinal cord or up to half a jawbone,” said Crump.

By studying zebrafish jaw repair, the team discovered that a special type of repair cell, called an “ossifying chondrocyte,” is necessary for effectively healing bone. The Crump and Mariani labs published these findings in the journal Development.

More recently, the team found that similar repair cells also enable mice to heal large-scale rib injuries.

To study these injuries further, Mariani recently secured a $2.4 million Research Project Grant from the NIH. Her lab will continue to focus on markedly improving bone healing.

“Each year, about 5 million people in the US have fractures that fail to heal successfully,” said Mariani. “By using our new bone regeneration model, we can identify the stem cells needed for successful bone healing. Going forward, we are investigating a promising biological factor that stimulates these cells to mediate repair.”

Lieberman and Crump will remain key collaborators as they continue to advance their findings.

“The collaboration has really been wonderful for gaining new insights, ” said Mariani, a principal investigator at USC’s stem cell research center. “I’m delighted that we can continue our work together in the years to come.”

Crump added: “By coming together, research moves more quickly ahead, because the basic researchers can focus on areas that may be more useful clinically.”

Lieberman agreed: “It’s great to have a team approach, looking at the problem from different vantage points.”

To continue to promote such synergy between clinician-scientists and basic researchers, Andy McMahon is spearheading the university-wide USC Stem Cell initiative, which brings together 100 scientists working to accelerate the progress from discoveries to cures.

“Collaborative clinician-scientists such as Dr. Lieberman contribute exponentially to the success of any basic research effort,” said McMahon, director of USC’s stem cell research center. “They bring a deep understanding of both the patient need and the clinical requirements—which are vital to translating stem cell research into the future of patient care.”

By Cristy Lytal